Nothing is more depressing than a cemetery that is a vast expanse of well tended, neatly clipped green lawn with artfully placed trees and, in the middle of the field, a serene fountain.

Nothing is more depressing than a cemetery that is a vast expanse of well tended, neatly clipped green lawn with artfully placed trees and, in the middle of the field, a serene fountain.

Regulation size, flat bronze or granite headstones are considerately recessed so as not to impede the Grim Mower’s weekly task of scything the grass to a uniform height. The personality of each resident below the sod is telegraphed via basic dates and, perhaps, a small decorative indication of lodge, loves or defining tragedy dotingly etched on these lozenges of tribute.

Devoid of life, these are deserts of the dead.

Even the compact military cemeteries of Normandy contain more personality. Precisely measured, meticulously laid rows of upright white tablets or crosses; rank, regiment and dates clearly carved, are order wrenched out of chaos. That moment at the gates, seeing the lines of white stretch away, stops thoughts, breath, numbs the heart with the sense of youth denied the chance to become old and stupid like, well, like me.

Even the compact military cemeteries of Normandy contain more personality. Precisely measured, meticulously laid rows of upright white tablets or crosses; rank, regiment and dates clearly carved, are order wrenched out of chaos. That moment at the gates, seeing the lines of white stretch away, stops thoughts, breath, numbs the heart with the sense of youth denied the chance to become old and stupid like, well, like me.

Reading one of these headstones it is possible to get a sense of who the man was when he felt the sun on his face or, if nothing else, a clue to his language, his flag, his final prayer.

Here is a 40 year old, probably a family man who left in mid-career to march beside the 18 year olds still here around him. Children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews in Saskatoon or Nepean or Lachine think of someone here every year for a morning when the jets fly overhead and the piper plays.

In Paris there is a place where the Grim Mower does not rule and residents are permitted to retain some personality.

In Paris there is a place where the Grim Mower does not rule and residents are permitted to retain some personality.

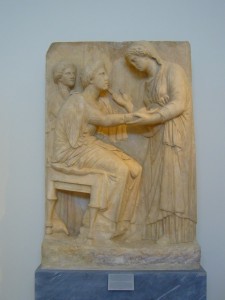

It is pretty obvious little has changed over the past 2500 years for a pile of dust that was once a Greek matron. But in the Athens museum we see her with the tenderness of those who loved her before she assumed the permanent status of ex-wife/mother/daughter-in-law.

It is pretty obvious little has changed over the past 2500 years for a pile of dust that was once a Greek matron. But in the Athens museum we see her with the tenderness of those who loved her before she assumed the permanent status of ex-wife/mother/daughter-in-law.

Some journeys are across oceans and some are through time. They all lead to the same discoveries: we love, we eat, we laugh, we live.